A few days ago Arlene called my attention to an email I got from the Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA) announcing an upcoming release of American Shad Fry into the Charles river. It sounded interesting and wasn’t too far from work, so I decided to go.

Shad are the biggest members of the herring family. Like other herring (and also like salmon), they live in the ocean most of their lives and swim up rivers to spawn. Anglers love them. They’re relatively big, challenging to catch, and good eating. They haven’t been breeding in the Charles since early in the industrial revolution, when the Charles was dammed for water power and there was no way for the fish to get upstream past the dams. Besides that, the Charles used to be badly polluted. The CRWA has been very active in helping enforce environmental laws and raising public awareness of the desirability of having a clean river, and by now the Charles is one of the cleanest urban rivers in the world. In recent decades fish ladders have been added to the dams, but fish ladders and clean water is not all it takes. The fish return to the river where they grew up, and if no fish have spawned in a river, no fish are going to return to it (except for a few strays, perhaps, but that’s not likely to establish a population.)

Fisheries biologists have found that it’s possible to re-establish a population of anadromous fish in a river by taking adult fish from one river, getting them to spawn in captivity, and stocking the baby fish in the river with no population of those fish. I’ve heard about that, and heard that it has worked in the Connecticut river. Here was my chance to learn about it in person.

Here’s an adult American Shad. This is a fish any fresh-water angler would be delighted to catch:

The US Fish and Wildlife Service had brought several hundred thousand shad to the Charles, but not that big. These were five days old, about the smallest fish I’ve ever seen. This bucket probably had a couple hundred of them:

In that picture, it looks like water with some pieces of lint in it, but the lint is fish! Each one is only about twice as long as a mosquito wriggler, maybe half an inch or three quarters of an inch long, transparent except for the eyes and backbone.

I got to the event in good time. There were two trucks parked close to the river, official US Fish and Wildlife Service flatbed trucks with big tanks on the back. One tank had several adult shad in it, including the one in the picture above. You could climb up on the truck to look in the tank. The F&W people were scrupulous about warning everyone, “Be careful! There’s nothing behind you to keep you from falling off!”

The other truck had a tank of the fry. It had a hose coming from the river which was bringing in river water so that the fry would be at river temperature when they were released — a sudden change of temperature wouldn’t be any good.

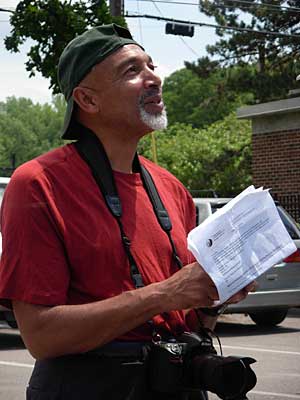

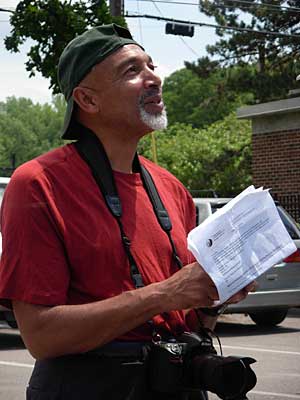

One of the first people to show up after me (the F&W people were there before me) was Derrick Z. Jackson, a Boston Globe columnist who writes almost as often about environmental issues as about social ones.

Two other spectators, who might have come to the river just to go fishing rather than watch the event, were this father & daughter:

Before any fish fry hit the water, the little girl had caught a sunfish. It doesn’t show in the picture, but it’s splashing there at her dad’s feet.

These folks spoke briefly.

I had been talking to the guy in the khaki before things really started; he’s from the US Fish and Wildlife Service. He was telling me about how successful the shad restocking efforts have been in many rivers, especially in the middle atlantic region. Perhaps the most interesting thing he told me was that all the fry have been marked so they can tell if fish they catch five years from now are wild fish or come from hatchery stock. How do you mark millions of fish fry that small? By adding some fluorescent dye to the water they’re in. If you want details, try this.

The woman on the right, in serious hip boots, is Mary Griffin, commissioner of the Massachusetts department of fish and wildlife. Later on she got to hold the hose that the fry were released through. The man in the middle is Bob Zimmerman, the director of the CRWA.

There were lots of people from the press, from local paper through community access TV to Boston Globe.

OK, now we’re getting ready to release the fish!

I love that smile. It really looks to me like, some days you have to spend all day worrying about a department budget and some days you have to spend all day arguing with legislators, but every so often you get to remember why you wanted to be a wildlife biologist and it’s all worth while.

And here’s Derrick getting his version of that last picture: